The Great Illusion: Secret Journal of Brexit (2016–2020)

Reviewed by Sébastien Goulard

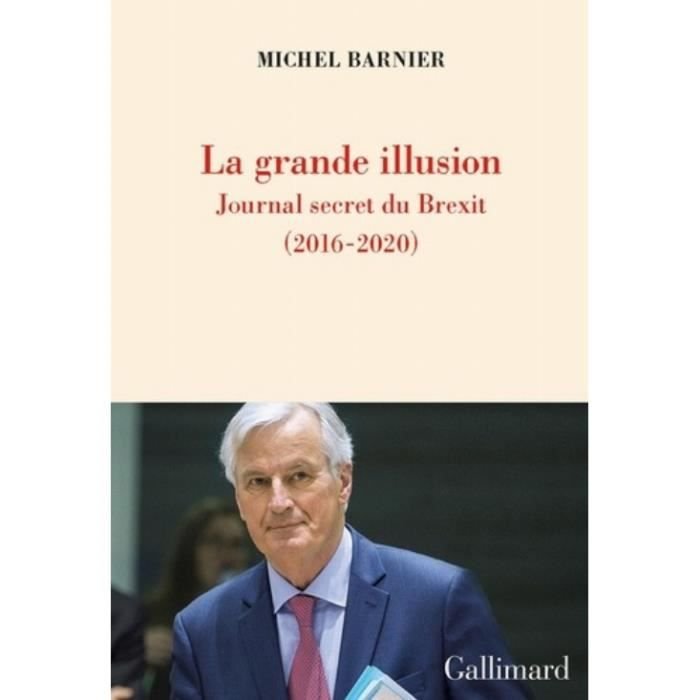

For almost four and a half years, Michel Barnier, former French Minister and European Commissioner, led negotiations on the United Kingdom’s exit from the European Union and the future relations between London and Brussels, following the British referendum on Brexit, held in June 2016. He relates what went on behind the scenes in a diary entitled “The great illusion: Secret journal of Brexit (2016–2020)”. This book immerses us in the long and bitter negotiations that have punctuated British and European political life since 2016.

Although we already know the result of these negotiations, namely the presentation of a trade and cooperation agreement between the European Union and the United Kingdom on 24 December 2020, this book keeps us going and describes the obstacles – but also mutual incomprehension – encountered by the parties during these negotiations.

What strikes us the most while reading this book is that the British side seems to have been rather unprepared for Brexit and its consequences. Announced in 2013 by Prime Minister David Cameron, the following British governments did not seem to understand the full repercussions of withdrawal from the European Union. We can only be surprised by the lack of a clear line, throughout the negotiations, on the future relationship between the UK and the European Union. The photo taken in July 2017 of the British negotiators (led by David Davis), without any dossier in front of them (unlike the European negotiators), illustrates this lack of preparation and is, of course, present in the book.

The British side seems to have decided on its Brexit strategy without having set an objective regarding relations with its main economic partner. For a long time, British negotiators defended an agreement such as the one concluded between the EU and Australia or the EU and Canada. But these agreements, which represent much less trade than there is between the United Kingdom and the European Union, themselves required long years of negotiations and were not easy to reach.

In fact, we soon came to realize that the goal of the British side was to continue having the widest possible access to the European market for its goods and services while retaining the possibility of not having to submit to European regulations so much with regard to social and environmental standards, which may create dumping threats from the United Kingdom. To achieve this result, the British tried some cherry picking and specific open negotiations, independent of one another; however, Michel Barnier and his team resisted and negotiated a global agreement outright.

What may seem almost shocking in the attitude of British negotiators is the disconnect between their positions and those of the majority of Brexit supporters. Of course, the return of a so-called sovereignty is at the centre of the issues, and the negotiators in fact insisted on Michel Barnier using this term at one press conference, to unblock the situation. But while some Brexit supporters (especially those in depressed regions of northern England) hoped that Brexit would protect them from the excesses of globalization, the goal of Boris Johnson and his ministers was quite different, since it consisted of opening up the British economy even more by transforming the country into a “Singapore-on-Thames”. Michel Barnier therefore qualifies – as a “great misunderstanding” – the principle of a global Britain as defended by Boris Johnson.

Another important aspect of British strategy was to play a waiting game and bet on the potential lack of patience of the Europeans, to drag out negotiations and thus accuse the European Union of not wanting to negotiate, using the blame game. But this strategy did not work. Likewise, a big difference between British and European negotiators is that the latter were all about the task at hand, while the British were subject to an extremely strong political influence. It should be noted that during these four long years, four British negotiators followed one another, each with his own style and his own interests, and this was reflected in the negotiations. In contrast, the Europeans have not changed their position since 2016, and Michel Barnier has enjoyed the full confidence of the Commission, the European Council, and leaders of member states.

The United Kingdom continued trying to break European solidarity during these four years by searching for allies on certain topics among the 27 members (and also among EU institutions) by attempting to create new negotiation fronts with the Commission, without going through the task force headed by Michel Barnier. But the British failed. Surprisingly, the 27 members showed solidarity with one another. Of course, each member had its own interests and its own red line when it came to negotiations with the UK. The team led by Michel Barnier cleared all potentially explosive subjects, such as the British bases in Cyprus, future relations between Spain and Gibraltar, and even (during the last few weeks) that of fishing rights. The most difficult issue, which Boris Johnson is currently challenging (in 2021), despite the Brexit agreement, and which is still problematic today, is of course that of Northern Ireland.

These negotiations also show that the European Union has the capacity to respond to the challenges it faces. Who knows what could be achieved by the EU and its allies/members if this much energy were to be deployed simultaneously on economic, environmental or security issues…One of the strengths of the European side, under Michel Barnier’s leadership, was its diversity. His team was made up of members from different countries, with varied backgrounds, and Michel Barnier did not hesitate to increase the number of meetings with leaders of different member states; he also met with students, entrepreneurs and European citizens throughout his mandate, and these meetings helped him negotiate. In contrast, the British seemed to become increasingly isolated and did not explain the consequences of Brexit to their own population.

Throughout this book, an overwhelming sense of mess and exhaustion is conveyed to the reader – all that energy and all those meetings to break up a relationship of over 40 years. One can wonder about the efforts made by London and Brussels to secure this divorce. These negotiations were, of course, necessary, but British unpreparedness mobilized unimaginable talents and resources, which could have been used for more constructive ends.

Throughout these negotiations and even today, now that relations between the European Union and the United Kingdom are theoretically defined, three subjects identified by Michel Barnier remain problematic – the Northern Irish question but also the integrity of the common market and the need for a strong partnership between the European Union and the United Kingdom.

During these four years, Michel Barnier traveled to Ireland on several occasions to hear the will of the Irish people. He explained the challenge – which did not seem to have been taken into account by the Brexiteers – of reaching a deal on Northern Ireland. To safeguard peace and respect for the Good Friday Agreement, it is not possible to create a physical border between the north and the south of the island. But at the same time, a situation cannot be permitted where there is no control over goods entering the European common market through Northern Ireland, where British standards are less stringent than European ones. The negotiations therefore focused on a system of control, now denounced by the British, between Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

Although the United Kingdom has left the European Union, the British have always hoped to have access to the common market and to certain aspects of the European Union, such as the free movement of capital, goods and services, but not that of persons, following the principle of “to have your cake and eat it”. For Michel Barnier, it was important that there were no distortions of competition in favour of British companies, which would have benefited from lower standards than those applicable to European companies.

A third point defended by Michel Barnier during his time in office was that of a strong partnership with the United Kingdom on certain issues regarding global governance, in particular on security, the fight against terrorism and climate change. On these issues, London and Brussels must continue to collaborate.

The format of the work, a diary, allows the reader to get to know its author quite well. This 500-page book reveals Barnier’s personality to us. He has had a long political career: Minister of the Environment from 1993 to 1995; Minister Delegate for European Affairs from 1995 to 1997; Minister of Foreign Affairs from 2004 to 2005; and finally, Minister of Agriculture and Fisheries from 2009 to 2010. He was then entrusted with the role of European Commissioner for the Internal Market and Services, under the chairmanship of José Manuel Barroso (2016–2019), before being appointed chief negotiator for talks with the United Kingdom. He is an accomplished politician who has nothing to prove to anyone. He knows how Brussels institutions work and knows how to talk to different people from different European countries. His personality did a lot to ensure that these negotiations were not a failure. Lesser men would have given up in the face of the procrastination, lack of will and even bad faith displayed by some British negotiators. He held on, which in itself was an achievement, and continued to engage in dialogue; to be available, even when there was little hope that a deal would be reached.

Michel Barnier evokes, in many passages, his Savoyard roots. It is, in fact, under his mandate as president of the General Council of Savoy, that Albertville was elected to be the host for the Winter Olympic Games in 1992. Even if Michel Barnier plays on this attachment to seem less like a European bureaucrat, there is a sense of genuineness about him.

Michel Barnier frequently refers to De Gaulle and only moderately appreciates it when a British negotiator quotes the former French president, in support of London’s position. His Gaullist commitment appears throughout his diary. It is, however, very difficult to know what position De Gaulle would have taken on Brexit today, having previously refused to integrate the United Kingdom into the Union. But references to De Gaulle seem outdated or even anachronistic in today’s France and Europe.

An important point to mention is that Michel Barnier did not forget to highlight the work of his collaborators. Of course, his own experience determined how he led these negotiations, but without the support of his team, the negotiations would not have been successful.

On the very last page of his diary, Michel Barnier announces his intention to continue to intervene in the public debate – in Europe but also in France. His rich experience, in particular that of Brexit, is invaluable in the face of current challenges. Michel Barnier is undoubtedly an accomplished statesman. However, he seems out of step with other political figures as he favours the long term over immediacy and meaningful dialogue over soundbites. He will have to make some effort not to appear like the “man from Brussels”. Quite unfairly, his fate is closely associated with the future of UK-EU relations; the difficulties or renouncement of the agreement between London and Brussels could be blamed on him, even if this book proves to us that, on the contrary, he devoted himself entirely to his mandate, with great dedication.

This journal, “The great illusion”, can be qualified as a historic book, and it will undoubtedly mark future analyses of Brexit. It shows how difficult it is for a European state to leave the European Union, not because Brussels would hold it against its will but because of our interdependence. Leaving the Union is far from easy because European economies and societies are extremely complex. Any Europeans who are thinking of leaving the Union would do well to give it serious consideration first.

Throughout this book, Michel Barnier proves to us that the European Union works; that the interests of each state are protected. However, having said this, it does highlight the issue of reforming the European Union to make its functioning more flexible and to reduce a certain arrogance on the part of officials in Brussels, as underlined by Michel Barnier. He is not in favour of a European federalism and believes that to better protect the interests of each state, the European Union is necessary, in particular vis-à-vis the other great powers.

The narrative style adopted by Michel Barnier is relatively simple and makes his topic accessible to all. It has the merit of explaining the functioning of European institutions, particularly relations between the three main institutions, the Commission, the European Council and Parliament, which some British negotiators pretended to discover. Yes, the functioning of the European Union is complex, but it allows a certain balance between member countries.

Of course, this book illustrates the vision of only one of the two parties. The British negotiators themselves may have felt frustration with the European position and no doubt have a different view of its negotiations. But Michel Barnier and former Prime Minister Theresa May held themselves in high regard during these negotiations, which seems less the case with her successor, Boris Johnson. Michel Barnier’s point of view is not neutral, but his desire to make the negotiations transparent, which was criticized by some British negotiators, shows a certain honesty in the face of the mandate entrusted to him.

Cookies are used on this site to improve the user experience.

By clicking on one of the links, you accept the use of cookies.